|

|

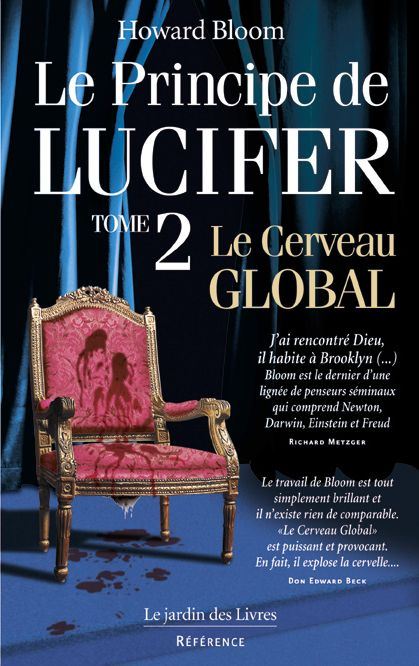

HRM-BULULU2 24,90 €

1 Derrick De Kerckhove. Connected Intelligence: The Arrival of the Web Society. Toronto : Somerville House Books, 1997, page 186.

2 Peter Russell. The Global Brain Awakens www.peterussell.com/GBAPreface.html août 1999.

3 Derrick De Kerckhove. Connected Intelligence.

4 B. Y. Chang et M. Dworkin. « Isolated Fibrils Rescue Cohesion and Development in the Dsp Mutant of Myxococcus Xanthus ». Journal of Bacteriology, décembre 1994, pages 7190-7196 ; James A. Shapiro. Communication personnelle. 24 septembre 1999.

5 W. D. Hamilton. « The Genetical Theory of Social Behaviour ». Journal of Theoretical Biology 7:1 (1964), pages 1-52.

6 William McDougall. An Introduction to Social Psychology. Boston : John W. Luce, 1908.

7 Walter B. Cannon. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hanger, Fear and Rage: An Account of Recent Researches into the Function of Emotional Excitement. New York : Appleton, 1915.

8 David Livingstone. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. New York : Harper & Brothers, 1860, cité par le Dr Daniel Goleman, Vital Lies, Simple Truths: The Psychology of Self-Deception. New York : Simon & Schuster, 1985, page 29.

9 Toutes les abeilles ouvrières sont des femelles. Les abeilles mâles sont célèbres pour la désinvolture de leur style de vie. On les appelle faux-bourdons.

10 W. D. Hamilton. « Altruism and Related Phenomena, Mainly in Social Insects ». Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 3, 1972, pages 193-232.

11 Voici une clause échappatoire post-hamiltonienne typique: vous vous rappelez que selon les partisans de la sélection individuelle, un animal, une plante ou un être humain abandonnera quelque chose uniquement si le bénéfice pour ses gènes est supérieur à ce qu'il jette. Au pire, l'abnégation d'un être généreux doit profiter à sa famille qui portent des gènes assez similaires aux siens. On appelle cela une « sélection de parenté ». Un être vivant peut abandonner une partie de ses biens pour un autre être vivant qui n'appartient pas à sa famille mais uniquement s'il a une bonne raison de s'attendre à être payé en retour. Cet échappatoire théorique est connu sous le nom d'« altruisme réciproque ». De toute façon, les règles d'un gène prospère restent les mêmes. Une créature est simplement le moyen qu'ont trouvé les gènes pour fabriquer encore plus d'autres gènes. Quel que soit le don d'une créature, les gènes doivent être largement remboursées.

12 David. C. Quelle, Joan E. Strassman et Colin R. Hughes. « Genetic Relatedness in Colonies of Tropical Wasps with Multiple Queens ». Science, novembre 1988, pages 1155-1157 ; Thomas D. Seeley. The Wisdom of the Hive: The Social Psychology of Honey Bee Colonies. Cambridge, Massachussetts : Harvard University Press, 1995, page 7.

13 A la recherche du babouin sacré. Hans Kummer. In Quest of the Sacred Baboon: A Scientist's Journey. Princeton University Press, 1995, pages 303-304.

14 D. S. Wilson et E. Sober. « Reintroducing Group Selection to the Human Behavioral Sciences ». Behavioral and Brain Sciences, décembre 1994, pages 585-654.

15 David Sloan Wilson. « Incorporating Group Selection into the Adaptationist Program: A Case Study Involving Human Decision Making ». Dans Evolutionary Social Psychology, éd. J. Simpson et D. Kendricks. Mahwah, New Jersey : Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997, pages 345-386.

16 Richard Dawkins. The Selfish Gene. New York : Oxford University Press, 1976 ; J. Philippe Rushton, Robin J. Russell et Pamela A. Wells. « Genetic Similarity Theory: Beyond Kin Selection ». Behavior Genetics, mai 1984, pages 179-193.

17 René A. Spitz. « Hospitalism: An Inquiry into the Genesis of Psychiatric Conditions in Early Childhood ». The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, vol. 1. New York International Universities Press, 1945, pages 53-74. Dr René A. Spitz, avec le Dr Katherine M. Wolf, « Anaclitic Depression: An Inquiry into the Genesis of Psychiatric Conditions in Early Childhood, II ». The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, vol. 2. New York International Universities Press, 1946.

* Dopplegänger : mythologie germanique. Le doppelgänger est une sorte de double qui prend progressivement la place de la personne "originale" (NdT).

* Ed. Jardin des Livres 2002. Disponible.

18 De René Spitz et Harry Harlow à Lydia Temoshok, Martin Seligman, Hans Kummer et Robert Sapolsky.

19 Avec une alimentation et une hygiène parfaites.

20 Marvin Zuckerman. « Good and Bad Humors: Biochemical Bases of Personality and Its Disorders ». Psychological Science, novembre 1995, page 330.

21 K. Sokolowski et H. D. Schmalt. « Emotional and Motivational Influences in an Affiliation Conflict Situation ». Zeitschrift für Experimentelle Psychologie, 43:3 (1996), pages 461-482.

22 Voir, par exemple, James S. House, Karl R. Landis et Debra Umberson. « Social Relationships and Health ». Science, 29 juillet 1988, page 541.

23 Bert N. Uchino, Darcy Uno et Julianne Holt-Lundstat. « Social Support, Physiological Processes, and Health ». Current Directions in Psychological Science, octobre 1999, pages 145-148.

24 B. M. Hagerty et R. A. Williams. « The Effects of Sense of Belonging, Social Support, Conflict, and Loneliness on Depression ». Nursing Research, juillet-août 1999, pages 215-219.

25 Erkki Ruoslahti. « Stretching Is Good for a Cell ». Science, 30 mai 1997, pages 1335-1346.

26 Cf., par exemple, B. Lown. « Sudden Cardiac Death: Behavioral Perspective ». Circulation, juillet 1987, pages 186-196 ; C. M. Jenkinson, R. J. Madeley, J. R. Mitchell et I. D. Turner. « The Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Survival after Myocardial Infarction ». Public Health, septembre 1993, pages 305-317.

27 Cf., par exemple, Michael Davies, Henry Davies et Kathryn Davies, Humankind the Gatherer-Hunter: From Earliest Times to Industry. Kent, R.-U. : Myddle-Brockton, 1992.

28 Pour obtenir plusieurs explications de ce type, voir : David P. Barash. The Hare and the Tortoise: Culture, Biology, and Human Nature. New York : Penguin Books, 1987 ; Richard E. Leakey et Roger Lewin. People of the Lake: Mankind and Its Beginnings. New York : Avon Books, 1983.

29 J'ai pris la liberté d'utiliser ici le mot « aimer » dans le cas des animaux. Dans le milieu scientifique, l'hypothèse selon laquelle les animaux ressentent des émotions tout comme les humains est largement considérée comme indémontrable, anthropocentrique et donc inacceptable. Néanmoins, le concept selon lequel les animaux ont, en fait, des sentiments semblables aux nôtres gagne du terrain. On trouvera en particulier 89 références savantes défendant les sentiments animaux d'attachement émotionnel - plus précisément, l'amour - dans le livre de Jeffrey Moussaieff et Susan McCarthy, When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals. New York : Delacorte, 1995, pages 64-90 et 247-250.

30 J. J. Lynch et I. F. McCarthy. « The Effect of Petting on a Classically Conditioned Emotional Response ». Behavioral Research and Therapy 5, 1967, pages 55-62 ; J. J. Lynch et I. F. McCarthy. « Social Responding in Dogs: Heart Rate Changes to a Person ». Psychophysiology 5, 1969, pages 389-393 ; N. Shanks, C. Renton, S. Zalcman et H. Anisman. « Influence of Change from Grouped to Individual Housing on a T-Cell-Dependent Immune Response in Mice: Antagonism by Diazepan ». Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, mars 1994, pages 497-502.

31 Charles Darwin. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. New York : D. Appleton, 1871, pages 146-148.

32 Pour en savoir plus sur le point de vue des partisans de la sélection de groupe, voir l'interprétation par Daniel G. Freedman de la théorie de l'équilibre de Sewall Wright (Daniel G. Freedman. Human Sociobiology: A Holistic Approach. New York : Free Press, 1979, page 5).

33 Thomas Welte, David Leitenberg, Bonnie N. Dittel, Basel K. al-Ramadi, Bing Xie, Yue E. Chin, Charles A. Janeway Jr, Alfred L. M. Bothwell, Kim Bottomly et Xin-Yuan Fu. « STAT5 Interaction with the T Cell Receptor Complex and Stimulation of T Cell Proliferation ». Science, 8 janvier 1999, pages 222-225 ; Polly Matzinger. « The Real Function of the Immune System or Tolerance and The Four D's (Danger, Death, Destruction and Distress) ». Vu sur : http://glamdring.ucsd.edu/others/aai/polly.html. Mars 1998.

34 Glaucia N. R. Vespa, Linda A. Lewis, Katherine R. Kozak, Miriana Moran, Julie T. Nguyen, Linda G. Baum et M. Carrie Miceli. « Galectin-1 Specifically Modulates TCR Signals to Enhance TCR Apoptosis but Inhibit IL-2 Production and Proliferation ». Journal of Immunology, 15 janvier 1999, pages 799-806.

35 M. E. Seligman. « Learned Helplessness ». Annual Review of Medicine ; W. R. Miller et M. E. Seligman. « Depression and Learned Helplessness in Man ». Journal of Abnormal Psychology, juin 1975, pages 228-238 ; William R. Miller, Robert A. Rosellini et Martin E. P. Seligman. « Learned Helplessness and Depression ». Dans Psychopathology, éd. Jack D. Maser et Martin E. P. Seligman.

36 Joseph V. Brady. « Ulcers in Executive Monkeys ». Scientific American, octobre 1958, pages 95-100.

37 On trouvera d'excellents débats sur les échecs de l'étude du singe exécutif dans : C. Robin Timmons et Leonard W. Hamilton. Drugs, Brains and Behavior. Publié chez Prentice-Hall sous le titre Principles of Behavioral Pharmacology. Mis à jour et disponible en ligne sur le site de la Rutgers University. www.rci.rutgers.edu/~lwh/drugs/. Janvier 1999 ; Paul Kenyon. Biological Bases of Behaviour: Stress and Behaviour. Plymouth, R.-U. : University of Plymouth, Everday and Executive Stress, janvier 1999. http://salmon.psy.plym.ac.uk/year1/STRESBEH.HTM

38 M. E. Seligman. « Learned Helplessness ». Annual Review of Medicine ; W. R. Miller et M. E. Seligman. « Depression and Learned Helplessness in Man ». Journal of Abnormal Psychology, juin 1975: page 228-238 ; William R. Miller, Robert A Rosellini et Martin E. P. Seligman. « Learned Helplessness and Depression ». Dans Psychopathology, éd. Jack D. Maser et Martin E. P. Seligman Ph D; Vital Lies, Simple Truth: The psychology of self-deception.

39 V. C. Wynne-Edwards. Animal Dispersion in Relation to Social Behaviour. New York : Hafner, 1962 ; V. C. Wynne-Edwards, Evolution through Group Selection. Oxford : Blackwell Scientific : 1986.

* En français dans le texte (NdT).

* Nom anglais du coq de bruyère. (NdT)

40 V. C. Wynne-Edwards. Evolution through Group Selection, page 87.

|

|